The background

Seed germination data describe the time until an event of interest occurs. In this sense, they are very similar to survival data, apart from the fact that we deal with a different (and less sad) event: germination instead of death. But, seed germination data are also similar to failure-time data, phenological data, time-to-remission data… the first point is: germination data are time-to-event data.

You may wonder: what’s the matter with time-to-event data? Do they have anything special? With few exceptions, all time-to-event data are affected by a certain form of uncertainty, which takes the name of ‘censoring’. It relates to the fact that the exact time of event may not be precisely know. I think it is good to give an example.

Let’s take a germination assay, where we put, say, 100 seeds in a Petri dish and make daily inspections. At each inspection, we count the number of germinated seeds. In the end, what have we learnt about the germination time of each seed? It is easy to note that we do not have a precise value, we only have an uncertainty interval. Let’s make three examples.

- If we found a germinated seed at the first inspection time, we only know that germination took place before the inspection (left-censoring).

- If we find a germinated seed at the second inspection time, we only know that germination took place somewhere between the first and the second inspection (interval-censoring).

- If we find an ungerminated seed at the end of the experiment, we only know that its germination time, if any, is higher than the duration of the experiment (right-censoring).

Censoring implies a lot of uncertainty, which is additional to other more common sources of uncertainty, such as the individual seed-to-seed variability or random errors in the manipulation process. Is censoring a problem? Yes, it is, although it is usually overlooked in seed science research. I made this point in a recent review (Onofri et al., 2019) and I would like to come back to this issue here. The second point is that the analyses of data from germination assays should always account for censoring.

Data analyses for germination assays

A swift search of literature shows that seed scientists are often interested in describing the time-course of germinations, for different plant species, in different environmental conditions. In simple terms, if we take a population of seeds and give it enough water, the individual seeds will start germinating. Their germination times will be different, due to natural seed-to-seed variability and, therefore, the proportion of germinated seeds will progressively and monotonically increase over time. However, this proportion will almost never reach 1, because, there will often be a fraction of seeds that will not germinate in the given conditions, because it is either dormant or nonviable.

In order to describe this progress to germination, a log-logistic function is often used:

G(t)=d1+exp{−b[log(t)−log(e)]}

where G is the fraction of germinated seeds at time t, d is the germinable fraction, e is the median germination time for the germinable fraction and b is the slope around the inflection point. The above model is sygmoidally shaped and it is symmetric on a log-time scale. The three parameters are biologically relevant, as they describe the three main features of seed germination, i.e. capability (d), speed (e) and uniformity (b).

My third point in this post is that The process of data analysis for germination data is often based on fitting a log-logistic (or similar) model to the observed counts.

Motivating example: a simulated dataset

Considering the above, we can simulate the results of a germination assay. Let’s take a 100-seed-sample from a population where we have 85% of germinable seeds (d=0.85), with a median germination time e=4.5 days and b=1.6. Obviously, this sample will not necessarily reflect the characteristics of the population. We can do this sampling in R, by using a three-steps approach.

Step 1: the ungerminated fraction

First, let’s simulate the number of germinated seeds, assuming a binomial distribution with a proportion of successes equal to 0.85. We use the random number generator ‘rbinom()’:

#Monte Carlo simulation - Step 1

d <- 0.85

set.seed(1234)

nGerm <- rbinom(1, 100, d)

nGerm

## [1] 89We see that, in this instance, 89 seeds germinated out of 100, which is not the expected 85%. This is a typical random fluctuation: indeed, we were lucky in selecting a good sample of seeds.

Step 2: germination times for the germinated fraction

Second, let’s simulate the germination times for these 89 germinable seeds, by drawing from a log-logistic distribution with b=1.6 and e=4.5. To this aim, we use the ‘rllogis()’ function in the ‘actuar’ package (Dutang et al., 2008):

#Monte Carlo simulation - Step 2

library(actuar)

b <- 1.6; e <- 4.5

Gtimes <- rllogis(nGerm, shape = b, scale = e)

Gtimes <- c(Gtimes, rep(Inf, 100 - nGerm))

Gtimes

## [1] 3.2936708 3.4089762 3.2842199 1.4401630 3.1381457 82.1611955

## [7] 9.4906364 2.9226745 4.3424551 2.7006042 4.0202158 8.0519663

## [13] 0.9492013 7.8199588 1.6163588 7.9661485 8.4641154 11.2879041

## [19] 9.5014360 7.2786264 7.5809838 12.7421713 32.7999661 9.9691944

## [25] 1.8137333 4.2197542 1.0218849 1.6604417 30.0352308 5.0235265

## [31] 8.5085067 7.5367739 4.4185382 11.5555259 2.1919263 10.6509339

## [37] 8.6857151 0.2185902 1.8377033 3.9362727 3.0864702 7.3804164

## [43] 3.2978782 7.0100360 4.4775843 2.8328842 4.6721090 9.1258796

## [49] 2.1485568 21.8749808 7.4265984 2.5148724 4.4491466 13.1132301

## [55] 4.4559642 4.5684584 2.2556488 11.8783556 1.5338755 1.4106592

## [61] 31.8419420 7.2666641 65.0154287 9.2798476 2.5988399 7.4612907

## [67] 4.4048509 27.7439121 3.8257187 15.4967751 1.1960785 62.5152642

## [73] 2.0169970 19.1134899 4.2891084 6.0420938 22.6521417 7.1946293

## [79] 2.9028993 0.9241876 4.8277336 13.8068124 4.0273655 10.8651761

## [85] 1.1509735 5.9593534 7.4009589 12.6839405 1.1698335 Inf

## [91] Inf Inf Inf Inf Inf Inf

## [97] Inf Inf Inf InfNow, we have a vector hosting 100 germination times (‘Gtimes’). Please, note that I added 11 infinite germination times, to represent non-germinable seeds.

Step 3: counts of germinated seeds

Unfortunately, due to the monitoring schedule, we cannot observe the exact germination time for each single seed in the sample; we can only count the seeds which have germinated between two assessment times. Therefore, as the third step, we simulate the observed counts, by assuming daily monitoring for 40 days.

obsT <- seq(1, 40, by=1) #Observation schedule

count <- table( cut(Gtimes, breaks = c(0, obsT)) )

count

##

## (0,1] (1,2] (2,3] (3,4] (4,5] (5,6] (6,7] (7,8] (8,9]

## 3 11 10 8 13 2 1 12 4

## (9,10] (10,11] (11,12] (12,13] (13,14] (14,15] (15,16] (16,17] (17,18]

## 5 2 3 2 2 0 1 0 0

## (18,19] (19,20] (20,21] (21,22] (22,23] (23,24] (24,25] (25,26] (26,27]

## 0 1 0 1 1 0 0 0 0

## (27,28] (28,29] (29,30] (30,31] (31,32] (32,33] (33,34] (34,35] (35,36]

## 1 0 0 1 1 1 0 0 0

## (36,37] (37,38] (38,39] (39,40]

## 0 0 0 0We can see that, e.g., 11 germinated seeds were counted at day 2; therefore they germinated between day 1 and day 2 and their real germination time is unknown, but included in the range between 1 and 2 (left-open and right-closed). This is a typical example of interval-censoring (see above).

We can also see that, in total, we counted 86 germinated seeds and, therefore, 14 seeds were still ungerminated at the end of the assay. For this simulation exercise, we know that 11 seeds were non-germinable and three seeds were germinable, but were not allowed enough time to germinate (look at the table above: there are 3 seeds with germination times higher than 40). In real life, this is another source of uncertainty: we might be able to ascertain whether these 14 seeds are viable or not (e.g. by using a tetrazolium test), but, if they are viable, we would never be able to tell whether they are dormant or their germination time is simply longer than the duration of the assay. In real life, we can only reach an uncertain conclusion: the germination time of the 14 ungerminated seeds is comprised between 40 days to infinity; this is an example of right-censoring.

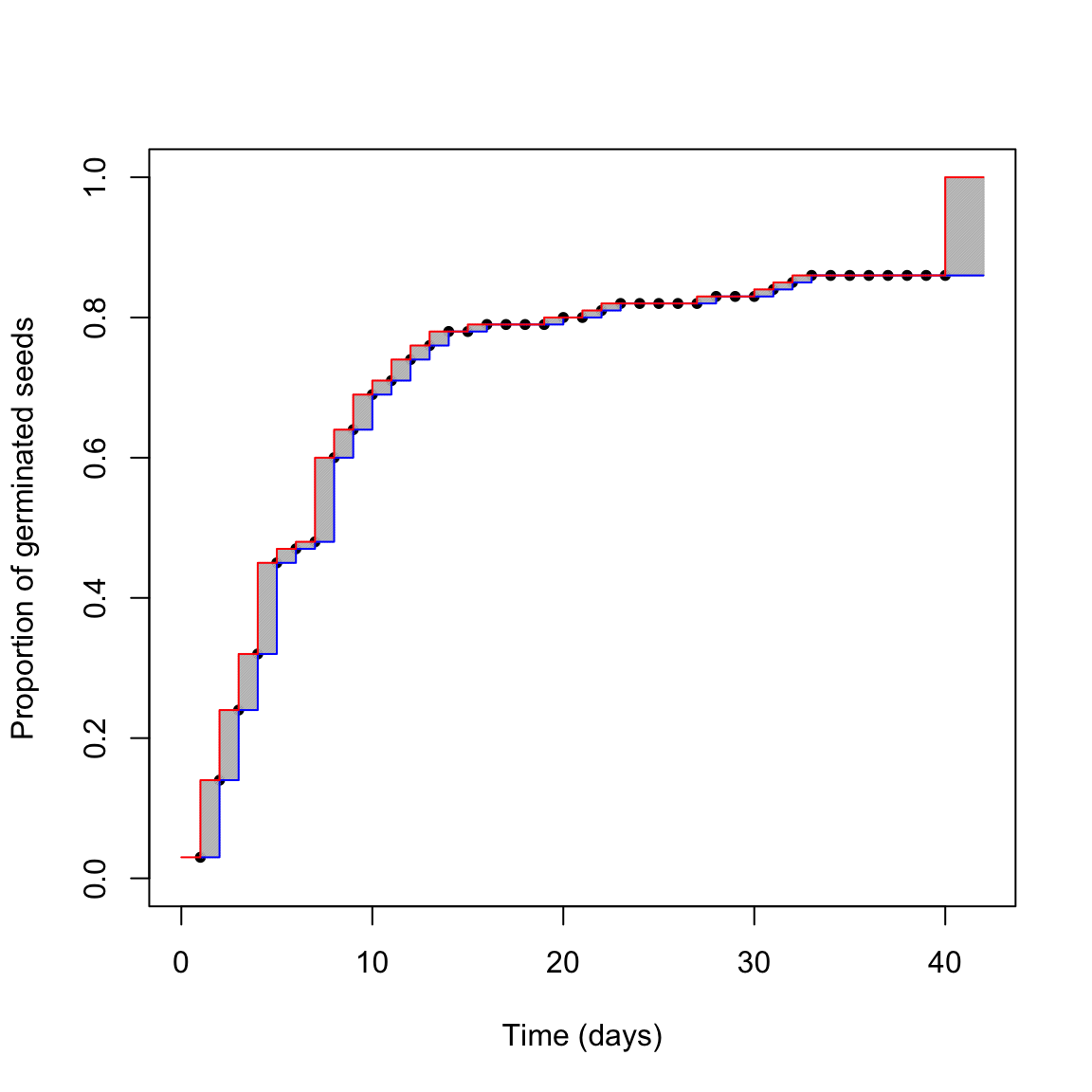

The above uncertainty affects our capability of describing the germination time-course from the observed data. We can try to picture the situation in the graph below.

What is the real germination time-course? The red one? The blue one? Something in between? We cannot really say this from our dataset, we are uncertain. The grey areas represent the uncertainty due to censoring. Do you think that we can reasonably neglect it?

Model fitting

The question is: how do we fit a log-logistic function to this dataset? We can either neglect censoring or account for it. Let’s see the differences.

Ignoring censoring

We have seen that the time-corse of germination can be described by using a log-logistic cumulative distribution function. Therefore, seed scientists are used to re-organising their data, as follows:

counts <- as.numeric( table( cut(Gtimes, breaks = c(0, obsT)) ) )

propCum <- cumsum(counts)/100

df <- data.frame(time = obsT, counts = counts, propCum = propCum)

df

## time counts propCum

## 1 1 3 0.03

## 2 2 11 0.14

## 3 3 10 0.24

## 4 4 8 0.32

## 5 5 13 0.45

## 6 6 2 0.47

## 7 7 1 0.48

## 8 8 12 0.60

## 9 9 4 0.64

## 10 10 5 0.69

## 11 11 2 0.71

## 12 12 3 0.74

## 13 13 2 0.76

## 14 14 2 0.78

## 15 15 0 0.78

## 16 16 1 0.79

## 17 17 0 0.79

## 18 18 0 0.79

## 19 19 0 0.79

## 20 20 1 0.80

## 21 21 0 0.80

## 22 22 1 0.81

## 23 23 1 0.82

## 24 24 0 0.82

## 25 25 0 0.82

## 26 26 0 0.82

## 27 27 0 0.82

## 28 28 1 0.83

## 29 29 0 0.83

## 30 30 0 0.83

## 31 31 1 0.84

## 32 32 1 0.85

## 33 33 1 0.86

## 34 34 0 0.86

## 35 35 0 0.86

## 36 36 0 0.86

## 37 37 0 0.86

## 38 38 0 0.86

## 39 39 0 0.86

## 40 40 0 0.86In practice, seed scientists often use the observed counts to determine the cumulative proportion (or percentage) of germinated seeds. The cumulative proportion (‘propCum’) is used as the response variable, while the observation time (‘time’) is used as the independent variable and a log-logistic function is fitted by non-linear least squares regression. Hope that you can clearly see that, by doing so, we totally neglect the grey areas in the figure above, we only look at the observed points.

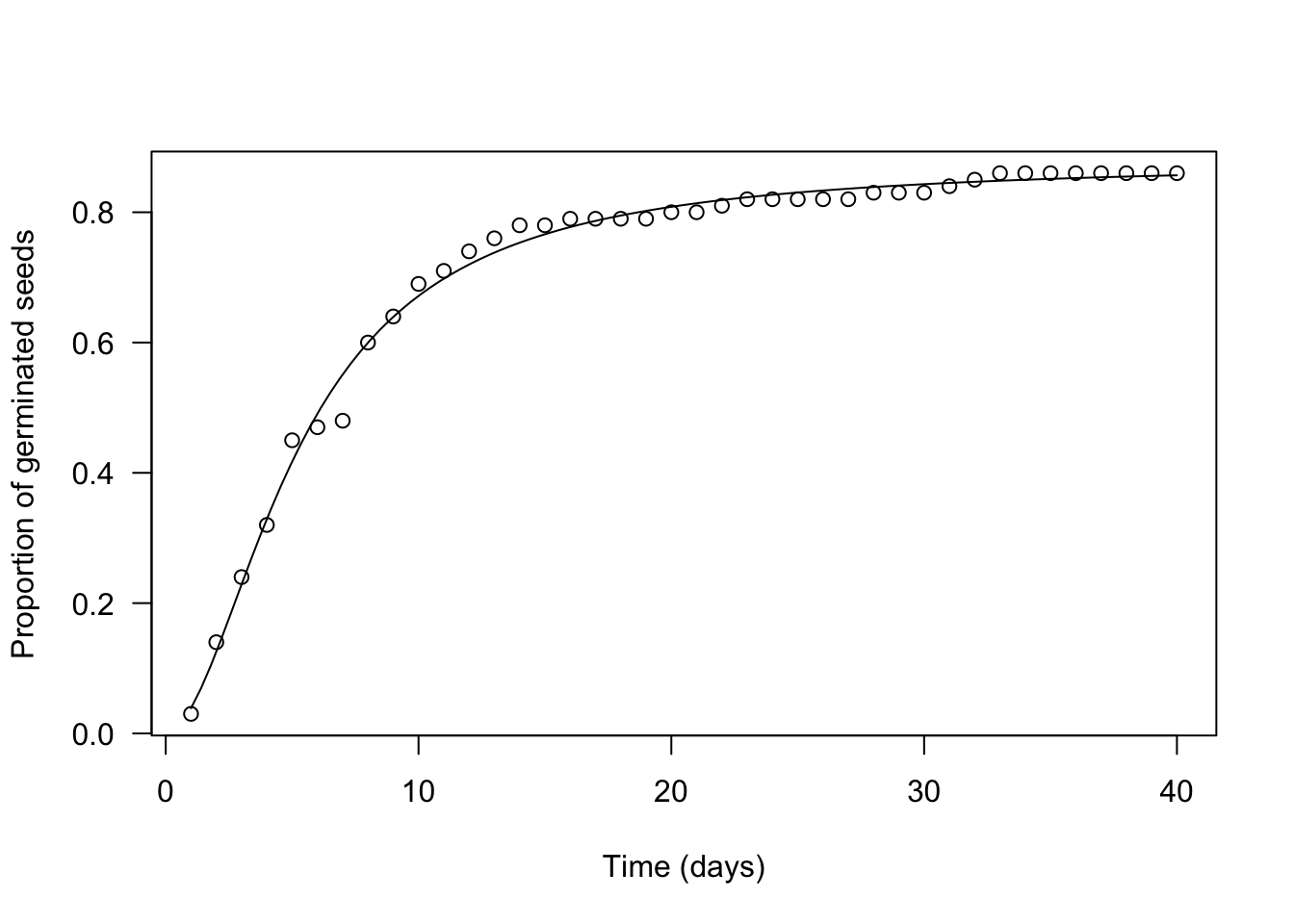

We can fit a nonlinear regression model by using the ‘drm’ function, in the ‘drc’ package (Ritz et al., 2015). The argument ‘fct’ is used to set the fitted function to log-logistic with three parameters (the equation above).

The ‘plot()’ and ‘summary()’ methods can be used to plot a graph and to retrieve the estimated parameters.

library(drc)

mod <- drm(propCum ~ time, data = df,

fct = LL.3() )

plot(mod, log = "",

xlab = "Time (days)",

ylab = "Proportion of germinated seeds")

summary(mod)

##

## Model fitted: Log-logistic (ED50 as parameter) with lower limit at 0 (3 parms)

##

## Parameter estimates:

##

## Estimate Std. Error t-value p-value

## b:(Intercept) -1.8497771 0.0702626 -26.327 < 2.2e-16 ***

## d:(Intercept) 0.8768793 0.0070126 125.044 < 2.2e-16 ***

## e:(Intercept) 5.2691575 0.1020457 51.635 < 2.2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1

##

## Residual standard error:

##

## 0.01762168 (37 degrees of freedom)We see that our estimates are very close to the real values (b = 1.85 vs. 1.6; e = 5.27 vs. 4.5; d = 0.88 vs. 0.86) and we also see that standard errors are rather small (the coefficient of variability goes from 1 to 4%). There is a difference in sign for b, which relates to the fact that the ‘LL.3()’ function in ‘drc’ removes the minus sign in the equation above. Please, disregard this aspect, which stems from the fact that the ‘drc’ package is rooted in pesticide bioassays.

Accounting for censoring

So far, we have totally neglected censoring. But, how can we account for it? The answer is simple: as with survival studies, we should use time-to-event methods, which are specifically devised to incorporate the uncertainty due to censoring. In medicine, the body of time-to-event methods goes under the name of survival analysis, which explains the title of my post. My colleagues and I have extensively talked about these methods in two of our recent papers and related appendices (Onofri et al., 2019; Onofri et al., 2018). Therefore, I will not go into detail, now.

I will just say that time-to-event methods directly consider the observed counts as the response variable. As the independent variable, they consider the extremes of each time interval (‘timeBef’ and ‘timeAf’; see below). In contrast to nonlinear regression, we do not need to transform the observed counts into cumulative proportions, as we did before. Furthermore, by using an interval as the independent variable, we inject into the model the uncertainty due to censoring.

df <- data.frame(timeBef = c(0, obsT), timeAf = c(obsT, Inf), counts = c(as.numeric(counts), 100 - sum(counts)) )

df

## timeBef timeAf counts

## 1 0 1 3

## 2 1 2 11

## 3 2 3 10

## 4 3 4 8

## 5 4 5 13

## 6 5 6 2

## 7 6 7 1

## 8 7 8 12

## 9 8 9 4

## 10 9 10 5

## 11 10 11 2

## 12 11 12 3

## 13 12 13 2

## 14 13 14 2

## 15 14 15 0

## 16 15 16 1

## 17 16 17 0

## 18 17 18 0

## 19 18 19 0

## 20 19 20 1

## 21 20 21 0

## 22 21 22 1

## 23 22 23 1

## 24 23 24 0

## 25 24 25 0

## 26 25 26 0

## 27 26 27 0

## 28 27 28 1

## 29 28 29 0

## 30 29 30 0

## 31 30 31 1

## 32 31 32 1

## 33 32 33 1

## 34 33 34 0

## 35 34 35 0

## 36 35 36 0

## 37 36 37 0

## 38 37 38 0

## 39 38 39 0

## 40 39 40 0

## 41 40 Inf 14Time-to-event models can be easily fitted by using the same function as we used above (the ‘drm()’ function in the ‘drc’ package). However, there are some important differences in the model call. The first one relate to model definition: a nonlinear regression model is defined as:

CumulativeProportion ~ timeAfOn the other hand, a time-to-event model is defined as:

Count ~ timeBef + timeAfA second difference is that we need to explicitly set the argument ‘type’, to ‘event’:

#Time-to-event model

modTE <- drm(counts ~ timeBef + timeAf, data = df,

fct = LL.3(), type = "event")

summary(modTE)

##

## Model fitted: Log-logistic (ED50 as parameter) with lower limit at 0 (3 parms)

##

## Parameter estimates:

##

## Estimate Std. Error t-value p-value

## b:(Intercept) -1.826006 0.194579 -9.3844 < 2.2e-16 ***

## d:(Intercept) 0.881476 0.036928 23.8701 < 2.2e-16 ***

## e:(Intercept) 5.302109 0.565273 9.3797 < 2.2e-16 ***

## ---

## Signif. codes: 0 '***' 0.001 '**' 0.01 '*' 0.05 '.' 0.1 ' ' 1With respect to the nonlinear regression fit, the estimates from a time-to-event fit are very similar, but the standard errors are much higher (the coefficient of variability now goes from 4 to 11%).

Neglecting or accounting for censoring?

You may wonder which of the two analysis is right and which is wrong. We cannot say this from just one dataset. However, we can repeat the Monte Carlo simulation above to extract 1000 samples, fit the model by using the two methods and retrieve parameter estimates and standard errors for each sample and method. We do this by using the code below (please, be patient… it may take some time).

GermSampling <- function(nSeeds, timeLast, stepOss, e, b, d){

#Draw a sample as above

nGerm <- rbinom(1, nSeeds, d)

Gtimes <- rllogis(nGerm, shape = b, scale = e)

Gtimes <- c(Gtimes, rep(Inf, 100 - nGerm))

#Generate the observed data

obsT <- seq(1, timeLast, by=stepOss)

counts <- as.numeric( table( cut(Gtimes, breaks = c(0, obsT)) ) )

propCum <- cumsum(counts)/nSeeds

timeBef <- c(0, obsT)

timeAf <- c(obsT, Inf)

counts <- c(counts, nSeeds - sum(counts))

#Calculate the T50 with two methods

mod <- drm(propCum ~ obsT, fct = LL.3() )

modTE <- drm(counts ~ timeBef + timeAf,

fct = LL.3(), type = "event")

c(b1 = summary(mod)[[3]][1,1],

ESb1 = summary(mod)[[3]][1,2],

b2 = summary(modTE)[[3]][1,1],

ESb2 = summary(modTE)[[3]][1,2],

d1 = summary(mod)[[3]][2,1],

ESd1 = summary(mod)[[3]][2,2],

d2 = summary(modTE)[[3]][2,1],

ESd2 = summary(modTE)[[3]][2,2],

e1 = summary(mod)[[3]][3,1],

ESe1 = summary(mod)[[3]][3,2],

e2 = summary(modTE)[[3]][3,1],

ESe2 = summary(modTE)[[3]][3,2] )

}

set.seed(1234)

result <- data.frame()

for (i in 1:1000) {

res <- GermSampling(100, 40, 1, 4.5, 1.6, 0.85)

result <- rbind(result, res)

}

names(result) <- c("b1", "ESb1", "b2", "ESb2",

"d1", "ESd1", "d2", "ESd2",

"e1", "ESe1", "e2", "ESe2")

result <- result[result$d2 > 0,]We have stored our results in the data frame ‘result’. The means of estimates obtained for both methods should be equal to the real values that we used for the simulation, which will ensure that estimators are unbiased. The means of standard errors (in brackets, below) should represent the real sample-to-sample variability, which may be obtained from the Monte Carlo standard deviation, i.e. from the standard deviation of the 1000 estimates for each parameter and method.

| b | d | e | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Nonlinear regression | 1.63 (0.051) | 0.85 (0.006) | 4.55 (0.086) |

| Time-to-event method | 1.62 (0.187) | 0.85 (0.041) | 4.55 (0.579) |

| Real values | 1.60 (0.188) | 0.85 (0.041) | 4.55 (0.593) |

We clearly see that both nonlinear regression and the time-to-event method lead to unbiased estimates of model parameters. However, standard errors from nonlinear regression are severely biased and underestimated. On the contrary, standard errors from time-to-event method are unbiased.

Take-home message

Censoring is peculiar to germination assays and other time-to-event studies. It may have a strong impact on the reliability of our standard errors and, consequently, on hypotheses testing. Therefore, censoring should never be neglected and time-to-event methods should necessarily be used for data analyses with germination assays. The body of time-to-event methods often goes under the name of ‘survival analysis’, which creates a direct link between survival data and germination data.

#References

- C. Dutang, V. Goulet and M. Pigeon (2008). actuar: An R Package for Actuarial Science. Journal of Statistical Software, vol. 25, no. 7, 1-37.

- Onofri, Andrea, Paolo Benincasa, M B Mesgaran, and Christian Ritz. 2018. Hydrothermal-Time-to-Event Models for Seed Germination. European Journal of Agronomy 101: 129–39.

- Onofri, Andrea, Hans Peter Piepho, and Marcin Kozak. 2019. Analysing Censored Data in Agricultural Research: A Review with Examples and Software Tips. Annals of Applied Biology, 174, 3-13.

- Ritz, C., F. Baty, J. C. Streibig, and D. Gerhard. 2015. Dose-Response Analysis Using R. PLOS ONE, 10 (e0146021, 12).